From the Starbucks Invasion to the Greening of Take-out

Written by Signe Langford

In Part One we explored the surprising origins of the take-out cup; here, we look ahead to the future.

Canadians love coffee at home and on the go. According to www.statista.com, in 2022 we perked, poured-over, pressed, and dripped approximately 5 million, 60-kilogram bags of the stuff; that’s about three cups per person, per day, and manufacturers of take-out cups and lids are constantly at work keeping up with that demand.

By the 1960s the take-out coffee scene had really started to heat up. Advances in technologies – coatings, materials, and manufacturing methods – were allowing designers and inventors to address all manner of to-go coffee cup quandaries: keeping contents hot and hands cool; lids that accommodated noses, latte foams, and protected walkers from spills; and adding colourful, custom designs and logos.

Things percolated along until Starbucks made the leap from a single California location to an international chain, hopping the US border and changing the to-go coffee landscape forever. Landing in Vancouver, B.C., on March 1, 1987, Starbucks gave us a whole new lingo, sizing, culture, and menu of coffee drinks, and with this, we entered the age of lattes, cappuccinos, and tall, foamy, whipped cream-topped concoctions – hot and cold. These dessert-in-a-cup drinks called for high, domed lids.

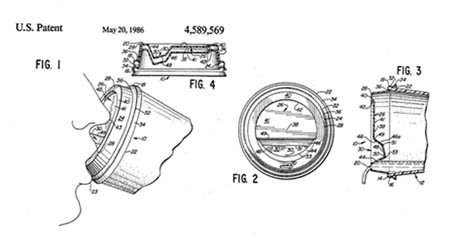

There are thousands of lid designs in service around the world, all boasting improvements to the to-go coffee drinking experience. Some are designed to cool the beverage slightly on its way to the mouth; some have divots for snapping the drinking flap into place; some look like a toddler’s sippy cup; but the lid considered the penultimate, is the Traveler lid by Solo, patented in 1984. It had it all: it was domed to accommodate foam and toppings; its rim design cooled the scorching drink; and it has a depression near the center for the drinker’s nose. But while to-go lid design had focused on a few aspects – the sipping spout, room for noses and foam – one aspect that had been ignored even though it had always been a less-than-lovely part of the hot coffee on the go experience, is the unpleasant smell of hot plastic – lids are mostly made from polystyrene – that hits the drinker before that first sip. In response, American inventor, Tim Sprunger, created the Arom-ahh lid, a disposable lid with a compartment housing enticing aromas meant to enhance the coffee while masking the hot plastic smell.

Meanwhile, on the cup front, the quiet rivalry between paper and foam came to a head in the late 1980s, as the environmental movement moved in from the fringe, spelling trouble for disposables in general and polystyrene in particular. But while polystyrene is a great insulator, and makes holding a cup of hot coffee painless, the optics of foam are bad; it doesn’t biodegrade, it floats on water; and it just comes across as less environmentally-friendly than paper. In the U.S., it was one buying decision made by Starbucks owner, Howard Schultz, to go with paper and not foam, that was the final nail in the standard, little, white foam coffee cup’s coffin.

Still, there are problems with paper too. Paper isn’t just paper; without an inner coating of polyurethane plastic, the cups would disintegrate from the moisture, and it’s this coating that renders most paper cups non-compostable, or recyclable. The other issue is paper’s lack of insulating power. Customers were asking to double up on the cup, creating more waste and costing the seller more per order. Enter the Ripple Cup, made of a thicker corrugated paper, and the coffee cup sleeve – The Java Jacket – invented in Portland, Oregon, in 1991, which soon became standard issue at all coffee shop counters. At the same time, manufacturers of paper cups were creating double- and triple-walled versions that kept coffee hotter for longer, and fingers safer; and by the mid-90s, in response to the infamous lawsuit – Liebeck v. McDonald’s – most to-go coffee cups would bear the message: “Caution: contents hot”.

Lids were introduced when it became clear coffee drinkers were sipping while walking, and presumably, slopping hot coffee on themselves. Likewise, as the suburbs grew and the daily auto commute lengthened, coffee was needed for the drive. The first patent for an auto cup holder was registered in 1953, but it wouldn’t be until 1984, with Chrysler’s Plymouth Voyager minivan, that the convenience would become standard issue.

Zooming through the day, take-out coffee in hand is still what most of us do, but the pandemic made us all slow down a bit; stop and smell the coffee, and with that, there’s been a renaissance of café culture, of sipping – not gulping – from ceramic instead of paper and plastic. The to-go cup isn’t going away just yet, but it is changing, keeping pace with consumers’ changing attitudes about time, throw-away culture, personal health and the health of the planet.

Consumers want cups and lids that can be composted, are made of sustainable materials and can be recycled, or used more than once, and they don’t want a side of micro-plastics or hormone-disrupting chemicals with their daily java jolt. According to Simon Fraser University, Canadians toss over 1.6 billion disposable coffee cups annually and 50 million trees are harvested every year to satisfy North America’s disposable coffee cup habit. But, a visit to the website www.trendhunter.com shows just how much thought and innovation is going into the future of to-go cups. From all around the world, inventors and innovators are imagining exciting new materials, and constructions all designed to reduce the footprint and improve each coffee-on-the-move experience.